Author: Sarah Christianson – 5 minute read

The Failure Project can be viewed at the bottom of the page

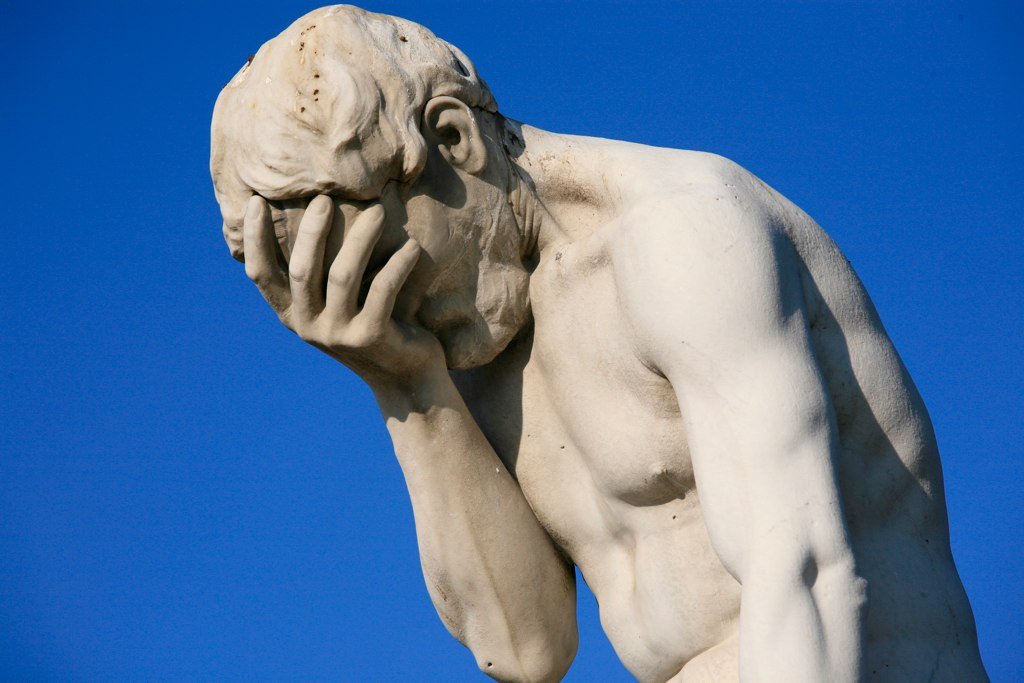

“Caïn venant de tuer son frère Abel” by Henri Vidal

Can you remember a time when you made a super embarrassing musical or professional mistake? Of course you can! These moments always seem to be deeply burned into our minds to forever haunt us and remind us of how we missed the mark. All of us in the Achelois Collective have moments like these, such as playing our worst in a rehearsal, making new mistakes in a performance, or succumbing to nervous habits in an audition. Even though these moments are common for all of us, we really don’t talk about them much, and in doing that, we’ve allowed ourselves to be isolated in our own worlds of failures.

What if we instead decided to not only discuss these moments with each other but share them with the world? Introducing the Failure Project: a crowdsourced database of our most embarrassing musical mistakes.

The idea behind the Failure Project came to me a few months ago after an orchestra rehearsal. I had played with this ensemble on-and-off for a number of years, but even so, there were a couple times throughout the years when I really did not jive well with the conductor. Going into this rehearsal, I remembered the shame I felt as I was called out from the podium, the sense of inadequacy I felt as they picked me apart in front of the whole group, and the overall sense of discouragement I felt in those moments. Time for rehearsal to start.

When I was playing, no matter how hard I tried to focus on the present and leave the past behind, all I could think of was failing. As a result, I obviously did not play my best. Thankfully I did not attract the conductor’s attention as I had before, but I still left that rehearsal feeling ashamed, inadequate, and discouraged about my musicianship. I figured that most musicians (if not all musicians) have felt this way at some point, but at the same time, I couldn’t remember a single conversation I had with other musicians about this topic. I felt so alone in my problem.

As I continued to dwell on these thoughts, I remembered an art piece I saw a while ago that dealt with failure head on. It was EITHER WE INSPIRE OR WE EXPIRE by artist Liam Gillick and data analyst Nate Silver (the guy that predicts the presidential elections). Their piece showcased various failed business trademarks in order to paint a more accurate picture of success in business.

I loved this piece. It was simple and direct: failure happens often, and this is how we will prove it!

I was struck by how the artists were able to convey major failures as ordinary occurrences. Not that they were trying to minimize the impact of failing, but that by making it seem commonplace, failure was shown to be a normal part of life rather than a defining moment.

What if I tried to view my failures this way, both as a common occurrence but also as something that can connect me with others? The Failure Project was born.

To create the project, we reached out to as many musicians as possible, asking them to share their musical failures. We included specific guidelines: stories must have taken place within the last 5 years, no specific identifying information, and no more than 250 characters. Reading through all the submissions, I noticed some common threads:

Every submission felt deeply personal. The performers all seemed to remember the details very clearly, as if each mistake had been stored in perfect record in the corners of their minds.

Each submission seemed to serve as a cathartic release for the performer. Whether or not they were submitted anonymously, it was obvious that the performers truly desired to get something off their chests.

The focus of each story wasn’t necessarily a moment of failure but how the performers themselves felt like failures.

Contributing to this project has helped me know that whenever I make a debilitating mistake, I’m not alone. I don’t have to hide my story or my feelings. But while sharing these moments certainly brings us together, will community alone help us to view failing in a better light?

After my “failed” rehearsal, I talked to a therapist friend of mine. She helped me realize that the reason I not only felt like a failure but further continued to make mistakes was because I had the wrong focus. I was thinking too much about how I would sound and what I would do instead of how the music should sound. Sure, we all want to sound our best. But when we concentrate on our personal performance in the moment, the music itself automatically takes a secondary role.

Since I hashed this out with my friend, I’ve made a conscious effort to focus more on the music, and these are the benefits I’ve noticed:

I have much more fun in every performance, which makes sense because playing music brings joy! When I was instead focused on my own performance, my joy was contingent upon success, and I often came up short.

I have much more confidence in my musicianship because I’m not trying to measure up to a standard of perfection. Instead, the standard of measurement is eliminated and replaced by a simple box to check: did I make music in this performance?

I’m not embarrassed by my failures. I still make mistakes, but they’re meaningless because they’re simply part of my musical performance, not a defining characteristic of my musicianship. And the mistakes I do make are relatively minor. I assume this is because my primary focus on the music limits the possibility for a major slipup.